Tassili n'Ajjer

Located between Libya and Algeria, the Tassili n’Ajjer plateau covers an area of 500 square kilometers.

In the language of the Tuareg, the nomads of this desert, Tassili n’Ajjer means “Plateau of rivers”, since this area is crossed by wadis, now dry riverbeds, through which water flowed in prehistoric times.

The mountain range is composed largely of sandstone. The erosion of the area has caused about 300 rock arches to form, as well as numerous other rock formations.

Due to the altitude and the properties of the sandstone, the vegetation is very rich, contrary to what happens in the surrounding desert. It includes, in the eastern and highest half of the chain, a vast variety of flora, among which the endemic and very rare species of the Sahara cypress and the Saharan myrtle stand out.

The ecology of Tassili n’Ajjer is that of Western Sahara. Many rivers flowed in this region millennia ago, testifying to an era in which the climate was very different from the present one.

The desert we see nowadays was fertile between twelve thousand and two thousand years ago, until a season of important climatic changes occurred, perhaps caused by celestial events (impact or passage near the earth’s orbit of large meteorites).

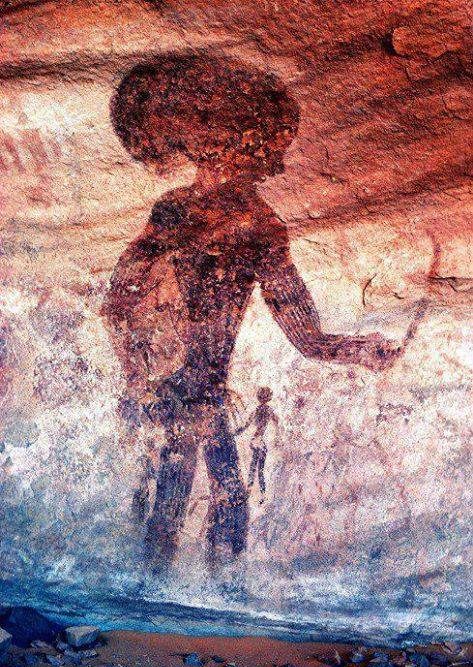

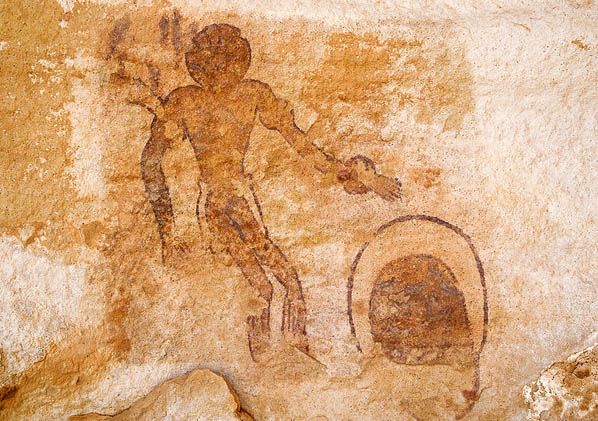

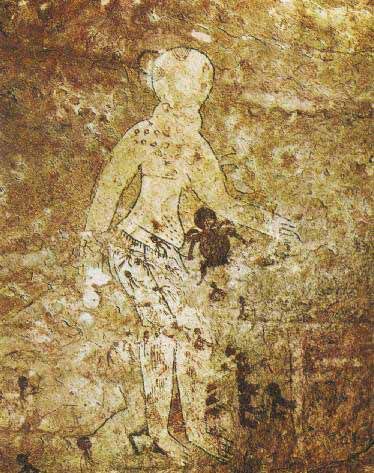

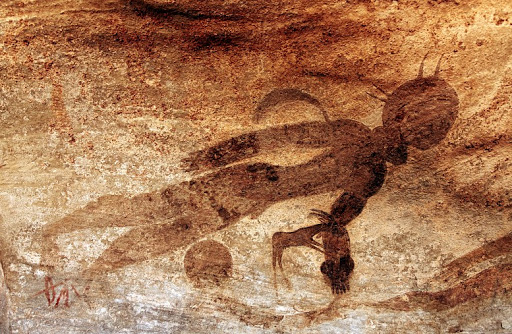

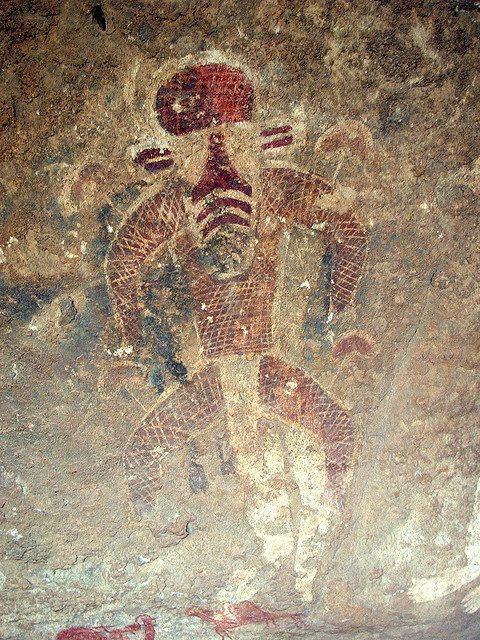

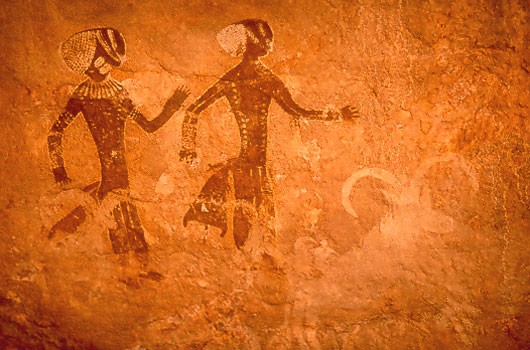

The area was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of the incredible collection of rock paintings discovered there, the most famous and interesting being about 8 thousand years old and represent anthropomorphic beings with round heads.

Those cave paintings date back to prehistoric times and depict animals that have now disappeared in the Sahara, hunting and sex scenes, a population of black-skinned shepherds together with another light-colored, bird-headed gods like the Egyptians, the largest, most evocative, and mysterious open-air art gallery in the world.

A feature so evident that the entire cultural period was named after that, the period of the “round heads”. The beings depicted with these heads also seemed to wear enigmatic clothing and appearing much taller than the figures in the same scene.

The discoverer of the paintings himself, the French archaeologist Henri Lhote in 1933, baptized one of the paintings “the great Martian god”.

In the Tassili range, in Séfar and Jabbaren, there are enigmatic figures who seem to swim or float in the void and others with round heads, who seem to wear helmets and diving suits or – as some have come to suppose – some kind of sophisticate costumes.

“In the Tuareg language – recalls Henri Lhote, the French archaeologist and discoverer of the paintings – Jabbaren means ‘the giants’ because there are prehistoric paintings with gigantic human images like a figure that is more than six meters high. You have to move away to see the whole figure at a glance, with a simple outline, the round head, with a single evident detail: a double oval in the center of the figure, which makes that character resemble our image of the Martians- but if the Martians ever set foot in the Sahara, it must have been many centuries ago, because those round-headed characters are, as far as we know, among the oldest paintings of the Tassili.”

Most of the anthropomorphic figures are interpreted by scholars and academics as the artistic production of the shamanic culture, attributing them to the ecstasy derived from the use of hallucinogenic substances.

The geographical extension of these artistic expressions is enormous and covers the entire belt of northern Africa, a sign of the great extension of the “green” Sahara. The period of these huge petroglyphs extends from 10000 to 6000 BCE, and human bodies appear represented with empty heads, devoid of features.

The second period, called “of the roundheads”, goes from 6000 to 5000 BCE. In this period the figures are enriched with colors obtained from natural lands, and sometimes human figures are represented with animal masks.

The third period is called Bovidian, from 5000 to 1800 BCE. In the rather elegant representations, painted in vivid colors, there are animals, including domestic animals, sheep, oxen, and scenes of everyday life.

Exceptional for prehistoric painting, the figures are first engraved in the rock, with flint tools, and then colored.

The cattle-herding people who appear in these paintings were, according to the great African historian Hampaté Bâ, the ancestors of the Peulh (Fulani), nomadic shepherds who later swarmed south to colonize the vast regions of Sudan and the Sahel. The white or reddish men, who are often seen in ‘symbiosis’ with the former, richly dressed, with customs very similar to the current ones, would have remained on the spot and would have been the ancestors of the Amazighs (known as Berbers, given to them by the ancient Greeks and Romans): the people of Atlantis, descended northwards from the Saharan massif of Ahaggar, as reported by Herodotus.

As he wrote in his chronicles: “The Atlantes inhabit a mountain called Atlas, from which they take their name” and indicates this mountain towards the south, twenty days’ walk (about 800 km) from the oasis of the Garamanti, the current Djerma, and ten days’ walk (about 400 km) from the Tassili massif, where the Ataranti lived: it can only be the Ahaggar massif, a sacred mountain of the Tuareg lineage. The chains that today we call with the name ‘Atlas’, arranged from west to east on three bands parallel to the Mediterranean coasts, are called ‘Deren’, according to their local name, given by the Berbers.