The Serapeum Of Saqqara

The Serapeum of Saqqara was discovered In 1850 by the French archaeologist Auguste Mariette.

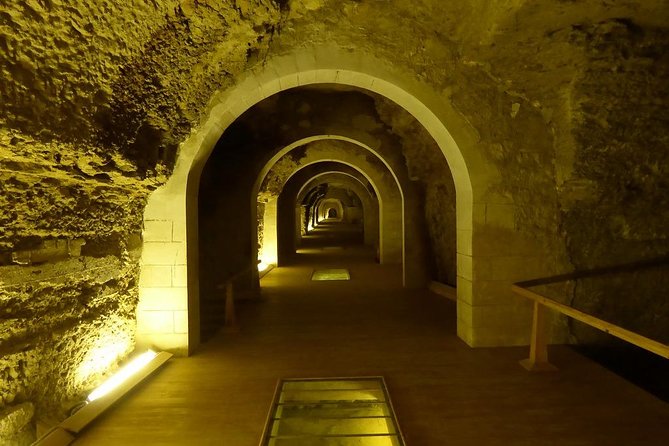

While digging near Saqqara, the team uncovered a long series of sphinxes that lined the driveway to an underground structure consisting of several underground tunnels.

When Mariette and his team managed to get inside, they found a series of galleries dug out of the limestone under a temple northwest of Djoser’s step pyramid.

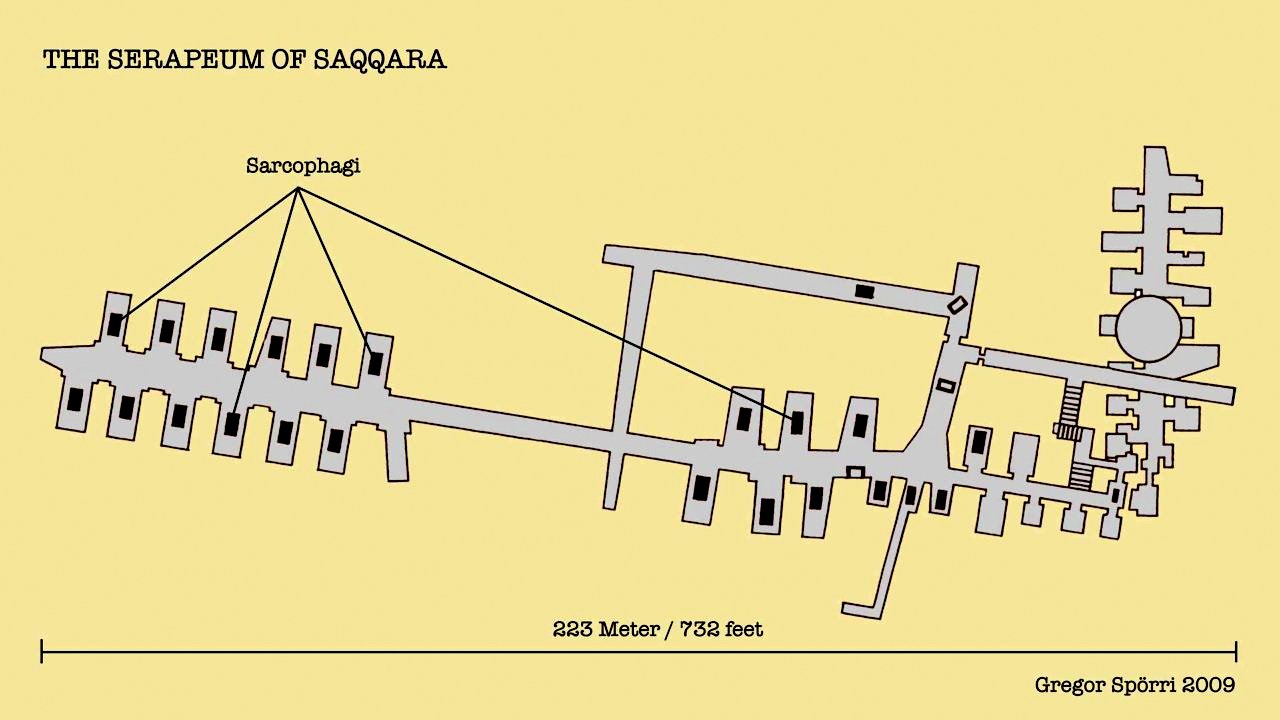

The smaller ones were catacombs, as the presence of wooden sarcophagi and other common funerary artifacts. The largest room, however, was nothing like the others.

The Great Gallery was in fact occupied by 24 large black granite boxes.

These were of much larger proportions than the other wooden sarcophagi found in the rest of the structure.

They measure over 3 meters in height and 4 in length, and over 2 in-depth, with a weight estimated at around 80 tons. Each box was inserted in a niche on a lowered floor.

Twenty-two out of the twenty-four boxes is perfectly placed in the middle of its niche, while two are off-centered.

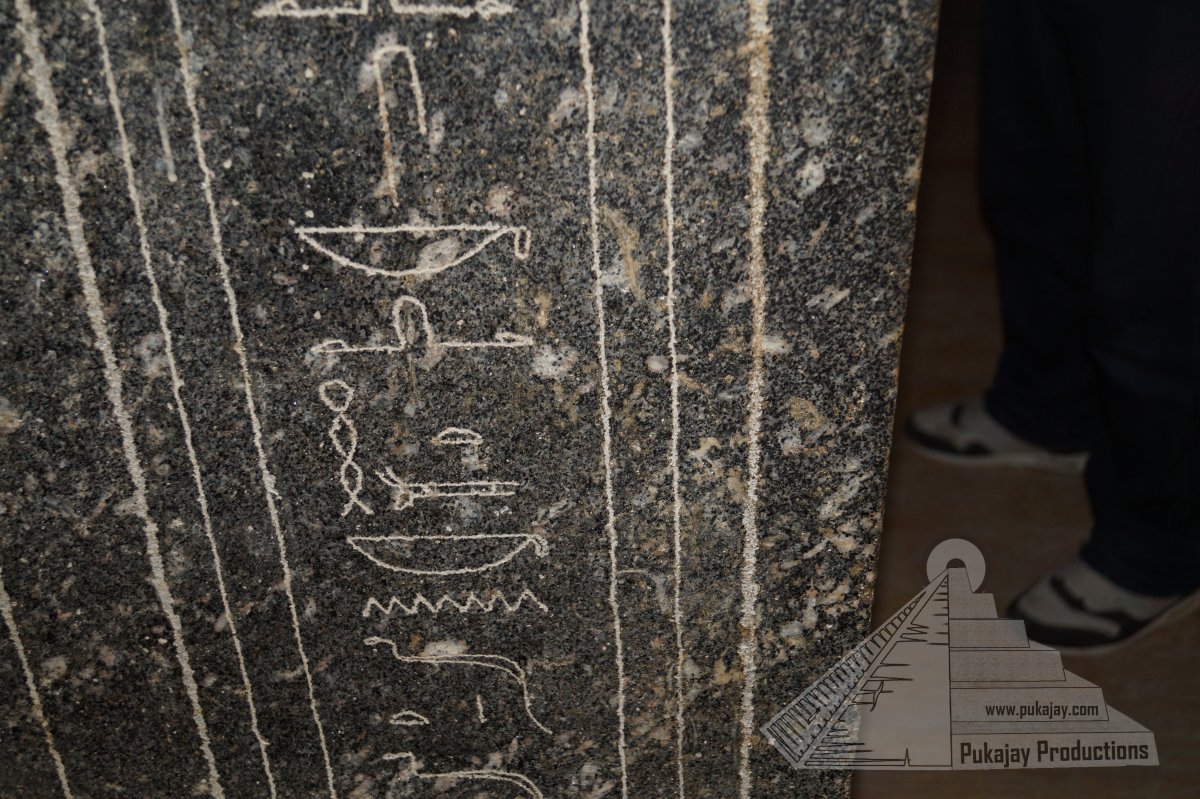

Only three of these imposing containers have rough-looking hieroglyphic inscriptions, as they are not carved with the same precision we’d expect from the builders of these boxes, whose cuts and polish were extremely sophisticated.

It doesn’t take a trained eye to realize that the builders of the sarcophagi had the knowledge to achieve extreme polishing on the granite surface, while the Egyptians that carved these hieroglyphs didn’t possess the same technique.

Official archaeology maintains that this place was a Serapeum, which is the name given to a temple dedicated to the syncretic goddess Serapis, a cult that unified elements of the cult of Osiris and the god Apis from the Hellenistic era in Egypt.

Embalmed bodies of bulls were often kept in a Serapeum, as the god Apis had the appearance of a bull, and that’s exactly what was found in many of the small wooden coffins discovered in the little tunnels.

Because of this, the team of archaeologists was convinced that the granite boxes of the great gallery also contained mummies of bulls and that such bodies were stolen in the past by tomb raiders.

As a matter of fact, all of the boxes were found completely empty.

Instead, plenty of normal wooden sarcophagi containing bulls was found, and they were made in the classic Egyptian style that one would expect.

Not only, but the supposed tomb raiders also had no interest in them.

To tighten the enigma, one of the sarcophagi contained a human mummy with incredible funerary artifacts and valuable objects, as well as steles and other precious jewelry.

What classic archaeology maintains is that a group of tomb raiders stole bull mummies inside the black granite boxes, but left the real treasure inside the galleries.

Simply put, there is zero evidence that some grave robber had passed through the galleries before Auguste Mariette.

There’s another interesting fact that makes it logically clear that no one tried to remove the 30 tons lids of the black granite boxes: to barely move one of such lids, Mariette and her team, by using the methods available at the time, decided to use explosives to peek inside of them.

Was a group of simple grave robbers from the past able to remove a 30 tons stone lid? How did they put them back into place? Why would a group of grave robbers make all that effort to steal bull mummies, leaving golden artifacts in their place?

The Serapeum of Saqqara is dated to 1300 BCE, but again the boxes do not present an ancient Egyptian crafting method, especially from that period.

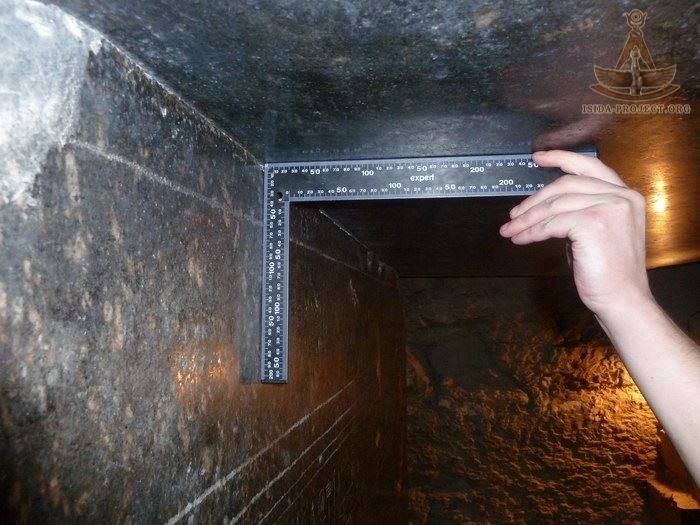

The outside of the boxes is not entirely perfect, but the interior has precise 90-degree angles carved into an ultra-polished granite surface.

The lids are not simple blocks of stone but are also carved on the inside, having cavities and protuberances.

Mariette makes no mention of hieroglyphs. The latter are numerous in the smaller galleries, but the granite sarcophagi are all clear but three of them.

The inscriptions on the three of the 24 boxes look like they were made at a later time.